Arizona History: Cochise, celebrated leader of the Chokonen band of Chiricahua Apaches of present day Arizona.

May 29, 2023

Chiricahua Apaches: 1886. Image by C.S. Fly, Tombstone photographer.

Cochise was a prominent leader of the Chiricahua band of Apache Indians during the mid-19th century. He played a crucial role in the resistance against American expansion into the traditional Apache lands in southern Arizona and northern Mexico. Cochise’s leadership, tactical prowess, and determination made him a revered figure among his people and a formidable opponent for the U.S. Army.

In popular culture, Cochise is eclipsed by Geronimo, who is revered as a great, resistant leader of his people. However, it should be noted that the people who followed Cochise remained and kept the Apache culture alive, while those who followed Geronimo perished almost entirely. Those who were in Geronimo’s tribe were shipped off to reservations far away in the east, and none live today in their native land of Arizona. Our contemporary knowledge of Apache culture is largely due to the ability of Cochise to secure the peace treaty, and find a way for his people to endure.

Cochise: Chiricahua Apache Chief (The Civilization of the American Indian Series) by Edwin R. Sweeney

When it acquired New Mexico and Arizona, the United States inherited the territory of a people who had been a thorn in side of Mexico since 1821 and Spain before that. Known collectively as Apaches, these Indians lived in diverse, widely scattered groups with many names—Mescaleros, Chiricahuas, and Jicarillas, to name but three. Much has been written about them and their leaders, such as Geronimo, Juh, Nana, Victorio, and Mangas Coloradas, but no one wrote extensively about the greatest leader of them all: Cochise.

Bronze bust of Cochise, sculpted by Betty Butts. Fort Bowie National Historic Site. National Park Service / A. Cassidy

At the time of Cochise’s youth, the political climate of southeastern Arizona and northeastern Sonora was fairly quiet. The region was under the control of the Spanish, who had skirmished with the Apaches and other tribes in the region but settled on a policy that brought a kind of peace. The Spanish aimed to replace Apache raiding with the provision of rations from established Spanish outposts called presidios.

This was a deliberately planned action on the part of the Spanish to disrupt and destroy the Apache social system. Rations were corn or wheat, meat, brown sugar, salt, and tobacco, as well as inferior guns, liquor, clothing and other items designed to make the Native Americans dependent on the Spanish. This did bring peace, which lasted nearly forty years, until near the end of the Mexican Revolution in 1821. The war seriously depleted the treasuries, rationing broke down slowly, and disappeared entirely when the Mexicans won the war.

As a result, the Apaches resumed their raiding, and the Mexicans retaliated. By 1831, when Cochise was 21 years old, hostilities were so extensive that, unlike earlier times, nearly all of the Apache bands under Mexican influence participated in raiding and conflicts.

Cochise, a Chiricahua, was said to be the most resourceful, most brutal, most feared Apache. He and his warriors raided in both Mexico and the United States, crossing the border both ways to obtain sanctuary after raids for cattle, horses, and other livestock.

In 1861, when his brother was executed by Americans at Apache Pass, Cochise declared war. He fought relentlessly for a decade, and then only in the face of overwhelming military superiority did he agree to a peace and accept the reservation. Nevertheless, even though he was blamed for virtually every subsequent Apache depredation in Arizona and New Mexico, he faithfully kept that peace until his death in 1874.****

Naiche, youngest known son of Chief Cochise. No photo of Cochise is known to exist, but many who knew both men said that Naiche looked a lot like his father.

Cochise was born around 1812 into the Chokonen band of the Apache tribe, which was part of the larger Chiricahua Apache group. He was born in the rugged Dragoon Mountains of present-day Arizona, an area that held great significance for the Apache people. As a young man, Cochise honed his skills in hunting, tracking, and warfare, becoming a respected warrior among his tribe.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dragoon_Mountains

The mid-19th century was a turbulent time for the Apache people as they faced encroachment and aggression from American settlers, as well as the Mexican government. Cochise’s leadership emerged during this period of conflict. In the early 1850s, tensions escalated when an American survey party led by Lieutenant George Bascom accused Cochise and his people of kidnapping a young boy and demanded their surrender. In what became known as the Bascom Affair, Cochise refused to comply and retaliated, sparking a prolonged conflict with the U.S. Army.

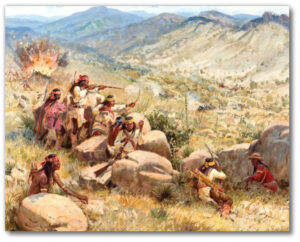

Chiricahuas under the leadership of Cochise ambush soldiers at Apache Pass. Painting by Joe Beler

Cochise’s military tactics were characterized by guerrilla warfare, ambushes, and hit-and-run tactics. He used the rugged terrain of the Chiricahua Mountains to his advantage, making it difficult for the U.S. Army to track and capture him. Cochise’s ability to outmaneuver and outwit his adversaries earned him a reputation as a formidable warrior and strategist.

Despite numerous military campaigns against him, Cochise remained a thorn in the side of American forces. He was never captured or defeated in battle, leading to a protracted stalemate between the Apache and the U.S. Army. In 1872, recognizing the futility of continued conflict, Cochise negotiated a peace treaty with the U.S. government. The treaty established a reservation for the Chiricahua Apache, allowing them to remain on their ancestral lands.

Cochise’s leadership extended beyond the battlefield. He was a skilled diplomat and advocate for his people’s rights. He fought tirelessly to protect Apache lands, culture, and way of life. Cochise’s leadership was characterized by his strong sense of loyalty and commitment to his tribe, making him a revered figure among the Apache people.

Cochise passed away on June 8, 1874, leaving behind a lasting legacy as a fierce warrior, a respected leader, and a symbol of Apache resistance. His efforts to defend his people’s sovereignty and their ancestral lands against overwhelming odds continue to inspire and resonate with Native American communities to this day. Cochise’s name is forever intertwined with the struggles and triumphs of the Chiricahua Apache, a testament to his enduring impact on the history of the American Southwest.

Following his escape, Cochise ambushed a wagon train and Butterfield stagecoach, taking prisoners of his own. Although both sides wanted to make an agreement, miscommunication and hostilities prevented it. Cochise tried to coordinate an exchange with Bascom, but Bascom refused. Cochise killed his prisoners,and the soldiers killed theirs in retaliation. Among the Apaches killed was Coyuntura, a favorite brother of Cochise. Cochise was devastated and furious.

One year later, in 1862, Chief Cochise and Chief Mangas Coloradas assembled the largest war party of the Apache Wars, roughly 200 warriors. With the advent of the Civil War, Union troops were stationed in the area to prevent the Confederacy from gaining the Southwest. On July 15, 1862, about 120 Union soldiers, part of the California Column, were marching east from Tucson. They were tired and thirsty. The soldiers made their way through Apache Pass toward Apache Spring near Fort Bowie. The Apaches probably saw an opportunity to plunder the military wagon train.

The Chiricahua attacked the soldiers from the hills above. The Battle of Apache Pass, one of the largest battles in the Apache Wars, ensued. The Chiricahua might have been successful had it not been for two Mountain Howitzer cannons.

In reference to the Mountain Howitzers, an Apache warrior stated, “We would’ve won if you hadn’t fired wagons at us.”

Bewildered by the destruction, the Chiricahua scattered and retreated. In the aftermath of the battle Mangas Coloradas was badly wounded. His warriors carried him all the way into Mexico where they threatened a doctor into helping him.

The first Fort Bowie was built near Apache Pass and Spring to guard the area from future attacks.

The Apache Wars, though long, were not fought in the manner of most wars. There were very few open battles. Ambushes were common. The Chiricahua did not consider retreat shameful, but a useful tactic. They would usually only engage in open battle if they had greater numbers, the higher ground, or the element of surprise. The Apache Wars lasted 24 years.

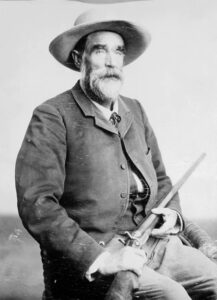

Tom Jeffords was the only white man Chief Cochise ever considered a friend.

–Public DomainChief Cochise began to operate primarily from the impregnable mountain rock formation known as Cochise Stronghold in the Dragoon Mountains. Tall rock spires allowed lookouts to see anyone approach from far off. Many hiding spots allowed for easy ambush. The Stronghold was never taken. Cochise still ranged across a huge area–from Tucson, Arizona to Mesilla, New Mexico, and from Safford, Arizona to several hundred miles into Mexico. The United States military sought Cochise, but he proved far too elusive when chased, and far too effective a commander in battle. He was also unrivaled with a spear. The Chiricahua people were more adapted to the land, better at hiding in it, and had better knowledge of it than United States soldiers. The military had many fights with Cochise and the Chiricahua Apache, but no single fight ended the war.

The people of the United States did not understand Native American culture very well. They did not understand the separation between tribes. For example, they often thought the actions of one tribe were directly tied to that of another. This was rarely the case. Lieutenant Howard B. Cushing fell victim to this very ignorance. Cushing was attempting to pursue Cochise while another Chiricahua leader, Juh, (pronounced “who”) was pursuing him. Every time Cushing’s party got in skirmishes with Juh, Cushing assumed he was closing in on Cochise. However, he could not have been farther from the truth. Juh’s band eventually ambushed and killed Cushing.

Finding or defeating Chief Cochise had proven futile for the U.S. Army. The strategy shifted to relocating him and the Chiricahua Apache to a reservation. Cochise was tired. He and his people had found life on the run and in hiding exhausting. The Chiricahua were very effective warriors. They were often able to take down many soldiers before falling. However, the U.S. had what appeared to be an inexhaustible supply of soldiers and provisions.

Chief Cochise was asked repeatedly to meet and discuss relocating his people to a reservation. He would always refuse because reservations at the time had poor conditions. The San Carlos Reservation, for instance, had bad water, rampant sickness, mandatory role call, and forced menial labor which the people believed beneath them as warriors. Cochise bided his time and continued to avoid capture and defeat.

Cochise began experiencing intense stomach pains and could not always eat. In 1874, he died of what was likely stomach cancer. The whereabouts of his grave are still unknown, though it is thought to be somewhere in his Stronghold. Cochise was one of the Chiricahua’s most effective leaders during the time of the Apache Wars. He was the only one able to bring prolonged peace and freedom to his people, even if it did not last long after his death.

With Cochise’s death, the Chiricahua were left without a strong central leader. The U.S. government saw a chance to close the problematic Chiricahua Reservation. The final straw came when two Chiricahua warriors killed two white men for not selling them whiskey. The government fired Agent Jeffords and abolished the reservation.

Around this time, John Clum became agent of the San Carlos Reservation in east central Arizona. He was a notoriously pompous man. The Apache would nickname him the “Turkey Gobbler” because they thought he walked like a turkey. Clum travelled to the Chiricahua Reservation to order all the Chiricahua people to the San Carlos Reservation. He met with Cochise’s son, Taza, who had taken up the mantle of chief as his father had prepared him to do. Also at the meeting was Juh, whose brother-in-law often spoke for him because Juh had a stutter. Juh’s brother-in-law’s name was Goyakla. He was also known as Geronimo.

Wikimedia, File: Geronimo (From L. D. Greene Album) – National Archives and Records Administration.