Carlos Montezuma –– The real life Arizona Yavapai-Apache culture hero you’ve never heard of.

June 10, 2023

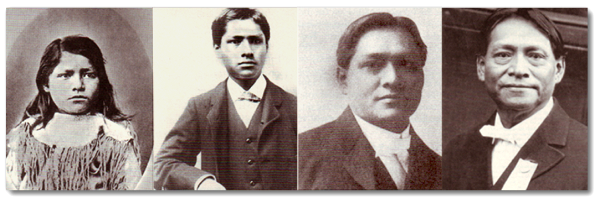

Carlos Montezuma or Wassaja (c. around the year 1866, somewhere near Four Peaks, Arizona – January 31, 1923) was a Yavapai – Apache Native American, activist, and founding member of the Society of American Indians. His birth name, Wassaja, means “Signaling” or “Beckoning” in his native tongue. [At the age of 5] Wassaja was kidnapped by Pima raiders along with other children to be sold or bartered. Wassaja was then purchased by an Italian photographer Carlo Gentile in Adamsville, for thirty silver dollars.

The late Carlos Montezuma (Wassaja) was a remarkable Native American figure in the 19th and early 20th centuries – a Native American of mixed heritage, a medical doctor, and a Native American activist. Despite a period of enslavement in his childhood, Montezuma went on to leave an indelible mark on history and was instrumental in fighting for the rights and freedoms of his people. Throughout his life, he was a champion of learning and an outspoken advocate of his people’s visions of a better future. This is the extraordinary story of Carlos Montezuma … his heritage, his contributions to education and medicine, and his impactful activism.

Yavapai boy Wassaja was sold by Pima raiders to an Italian rescuer, who gave him a new name.

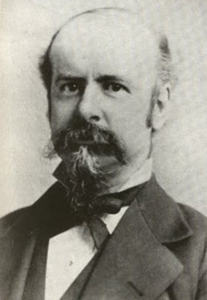

Carlos Montezuma. Chicago, June 6, 1874.

In the predawn darkness one day in October 1871 war whoops startled the inhabitants of a Yavapai village atop a plateau known as Iron Peak near Four Peaks in central Arizona Territory.

With the Yavapai warriors away from camp, the Pimas attacked the group of mostly women and children, killing 30 Yavapais. They spared some 16 to 18 children, including a 5-year-old boy named Wassaja and his two sisters. Taken into captivity, the siblings were soon separated.

A week later three Pimas took Wassaja south to the town of Adamsville, intent on selling him. Neapolitan photographer and adventurer Carlo Gentile was in town that day. Filled with compassion at the sight of the terrified, dirt-encrusted boy, Gentile handed the Pimas 30 silver dollars. With a nod, they handed over their captive. The providential encounter forever altered the direction of young Wassaja’s life.

Life with Gentile exposed Montezuma to a world vastly different from his own. Immersed in a foreign environment, he adapted and learned both English and Italian. Moreover, Gentile’s profession as a photographer introduced Montezuma to the art of capturing moments, an affinity that would stay with him throughout his life.

Carlo Gentile (1835-1893), a 19th-century Italian-American photographer.

After adopting his son, Gentile continued to travel extensively, and by December 1872, the two found themselves in Chicago, where they joined the production of a show entitled “The Scouts of the Prairie, and Red Deviltry As It Is!” at Nixon’s Amphitheatre. The chief draw was Buffalo Bill and “several live Indians,” including Carlos, who was billed as “the young Apache captive, Azteka.” Gentile photographed cast members and sold carte-de-visites (small mounted photos). They traveled with the show until March 1873 and then led a somewhat nomadic life until settling back in Chicago in 1875, where Gentile opened a photographic studio at the southeast corner of State and Washington streets, and Carlos started attending school.

Montezuma proved to be an outstanding student and graduated with honors from Urbana High School in 1879, at the age of just thirteen. A year later, he entered the University of Illinois where he studied English, mathematics, German, physiology, microscopy, zoology, mineralogy, physics, mental science, logic, constitutional history, political economy, geology, and chemistry.

Carlo Gentile was born in Naples, Italy, and had traveled the world before settling in British Columbia, Canada in the 1860s, where he undertook ethnographic work to document the First Nations peoples. In 1867, he relocated to California, moving back and forth between there and the Arizona Territory, where he documented the Pima and Maricopa Indians.

After several more years of travel, Gentile sent Montezuma to live with Rev. William H. Stedman in Urbana, IL, where he could have a more stable life.

Montezuma was just 14 years old when he matriculated at the University of Illinois in 1880. He wrote articles for the student newspaper and was the president of his class, as well as the president of the Adelphic Debate Society. In 1884 he graduated with a BS in Chemistry, the first Native American student to earn a degree from the University of Illinois. Immediately, Montezuma moved back to Chicago to pursue medicine. He was introduced to John H. Hollister, MD, a founder of Chicago Medical College and the professor of clinical medicine at that time, who promised to remit his tuition. In order to support himself through school, Montezuma worked at a pharmacy and received some financial help from friends. He was originally part of the Class of 1888, but it took him 5 years to finish school because he had to work so much. He officially graduated in 1889, though he built lifelong friendships with those in his original class, such as Charles Mayo. Montezuma became the second American Indian to earn an MD in the United States, the first being Susan La Flesche Picotte, MD.

In 1913 Montezuma married Marie Keller and continued practicing medicine and advocacy work throughout the rest of his life. He opposed the government sending Native soldiers to fight in World War I when they were denied US citizenship and continued to fight the Indian Bureau over Yavapai land and water rights. He was ultimately successful in ensuring the Yavapai had their own reservation on a portion of their ancestral lands and were not forced onto the nearby Salt River Pima-Maricopa Reservation.

Carlos Montezuma (standing second row, far right) Northwestern University Medical School, Class of 1889 Reunion Rochester, Minnesota, June 17–18, 1921

Montezuma’s journey to self-discovery continued as he sought to acquire an education that would empower him to fight for the rights of Native Americans. Despite facing the harsh realities of assimilation and cultural suppression at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, Montezuma refused to allow his spirit to be crushed. He saw through the school’s intentions and recognized the importance of preserving his heritage. Dissatisfied with Carlisle, Montezuma made a bold decision to leave and pursue a higher education.

In 1884, he enrolled at Chicago Medical College, now Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, marking his place in history as the first Native American student at the institution. The university became a beacon of hope for Montezuma, where he excelled in his studies, demonstrating his intellectual prowess and dedication. In 1889, he proudly walked across the stage to receive his medical degree, solidifying his commitment to healing and serving his community.

Montezuma’s activism extended far beyond healthcare. In 1911, he played a pivotal role in establishing the Society of American Indians, a groundbreaking national organization advocating for Native American rights. Through this platform, Montezuma fought tirelessly to dismantle the oppressive Bureau of Indian Affairs and challenge the reservation system that perpetuated inequality and stripped Indigenous communities of their autonomy.

Hektoen International Journal…

Montezuma’s own evolving views were complex and not easy to describe. His opposition to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, initially undertaken on the grounds that it inhibited opportunities for assimilation, was further fueled by his involvement in the Yavapai’s resistance to the Bureau’s abridgment of their land and water rights at the McDowell reservation in Arizona. It was at this point that he first presented his best-known tract, “Let My People Go” to the Society of American Indians in 1915. His relative mobility and stature made him an extremely successful spokesman, and he became known in Washington as a troublemaker—far more effective than the uneducated and compliant constituency they imagined.

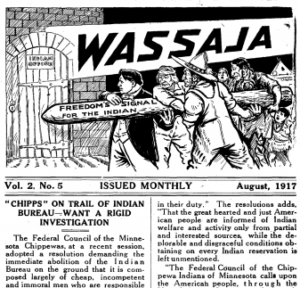

The Arizona State University Libraries digital repository contains 49 digitized volumes of the Wassaja newsletter.

His advocacy efforts gained Montezuma national prominence. His speech “Let My People Go” was read in Congress in 1916 and appeared in the Congressional Record.

Recognizing the power of media, Montezuma also created and published a monthly magazine called Wassaja in 1916, where he fearlessly tackled these issues, spreading awareness and inspiring Montezuma’s magazine, Wassaja, became a powerful vehicle for his activism. Its pages were filled with thought-provoking articles, stirring poetry, and poignant photography, capturing the essence of Native American culture and the harsh realities they faced. Through the publication, Montezuma connected with like-minded individuals, sparking conversations, and fostering a sense of unity and purpose among Native American communities across the nation. Wassaja was published every month until November 1922 (the last issue appearing just two months before Montezuma passed), at five cents a copy.

Although Montezuma’s life was tragically cut short with his passing in 1923, his legacy lives on. His unwavering dedication to justice and equality continues to inspire Native Americans and all those who fight for marginalized communities. His work laid the foundation for future generations of activists, empowering them to confront the systemic injustices that persist to this day.

Today, Native American activists and leaders draw inspiration from Montezuma’s life story. They carry his torch, fighting for the recognition of tribal sovereignty, cultural preservation, and equitable opportunities in education, healthcare, and representation. Through their collective efforts, they honor Montezuma’s legacy and strive to create a more inclusive and just society.

Carlos Montezuma’s life was a testament to the indomitable spirit of Native American resilience and activism. From his early years as a kidnapped child to his accomplishments as a medical professional, Montezuma defied the odds and overcame adversity. His pursuit of education and his relentless advocacy for Native American rights left an indelible mark on history. Through his work, Montezuma instilled hope, galvanized communities, and challenged oppressive systems. His story serves as a reminder that the fight for justice is ongoing and that every individual, regardless of their background, has the power to effect change. Carlos Montezuma’s legacy will forever be intertwined with the ongoing struggle for equality and the pursuit of a more inclusive society.

Historical Marker Location: 33° 34.705′ N, 111° 41.017′ W.

Marker is near Fort McDowell, Arizona, in Maricopa County. Marker is on Beeline Highway (Arizona Route 87 at milepost 190) near North Fort McDowell Road, on the right when traveling north.

GUIDE AND INDEX to the PAPERS OF CARLOS MONTEZUMA, M.D., 1871-1952

including the papers of MARIA KELLER MONTEZUMA MOORE, 1910-1952

and JOSEPH W. LATIMER, 1911-1934

Indexed Chronology, biographical notes, correspondence, speeches, essays, medical notes, financial material, and a virtually complete run of Dr. Montezuma’s newsletter, Wassaja. Also included are letters and publications of Carlos Montezuma’s attorney, Joseph W. Latimer, and the correspondence of his wife, Maria Keller Montezuma Moore. The documents in this edition are drawn from over forty repositories and roughly sixty newspapers and periodicals.

Carlos Montezuma: Changing is Not Vanishing

Produced by the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign